über die Literaturtechniken in der Zweitsprache

Essay und literarische Umfrage

Im Zuge meiner Recherche zum zweitsprachigen Schreiben als Mutation habe ich Schreibkolleginnen angefragt in Bezug auf ihren Schreibprozess als mehrsprachige Autor*innen. Hier ist die Antwort von Seda Tunç.

In the course of my research on the second language writing as mutation I have asked writing colleagues to give their thoughts on how they perceive their own writing process as multilingual authors. Here is Seda Tunç’s answer.

Stimmt du der Mutation Metapher für das literarische Schreiben in der Zweitsprache zu? Wenn ja, warum? Wenn nein, warum?

Mut, Mute, Imitation. Mimesis.

Mutation kommt von ‘mutare’: ‘to change (something, voice, etc./transitive), to change (oneself into something /reflexive), to change (intransitive). Three times change. In der Genetik geht dies so weit, dass es eine DNA Veränderung bedeutet. Mir passiert etwas im Tempo, in der Temporarität der Zeit, was aber gleichzeitig durch die Existenz der Pluralität -der aktiven Sprachen- immer bereit bleibt zu passieren. Und so frage ich mich auch, wie Mutation und Metamorphose miteinander verbunden sind, ob Mutation das Innere einer Metamorphose ist? Ein paar sich verkörperte Formen von diesem sich-durch-die Wirkung-einer-oder-mehreren-Sprachen-geändertenInnere treffe ich unter der Haut der Wörter. Wenn mehrere Sprachen mit einander infiltrieren, dann ist die Möglichkeit höher, dass mir drinnen etwas passiert. Aber was ist das? Ich erinnere mich an einen Satz im The Five Objections von Lars von Trier und Jorgen Leth: Today I experienced something that I hope to understand in a few days.

Wie fühlst sich die Mutation Metapher im Rahmen deiner eigenen Schreiberfahrung in der Zweitsprache an?

In welcher Sprache habe ich heute Nacht geträumt? In welcher diese Frage gedacht? Ist eine Reihung nicht mehr möglich und ist es nun Pluralität und eine kontinuierliche Cross-Verwandlung, die nicht mehr kategorisierbar ist? Es ist gut, wenn die Sprache außer Kontrolle gerät. Mutation in einer zweiten Sprache ist eine integrale Schere, die die Funktionalität und Notwendigkeit einer physischen Schere übernimmt um eine Art der Linearität und seine Enge zu enthärten. Und vielleicht bringt diese Schere die Verschiedenheiten zusammen, die nicht mehr von einander zum unterscheiden sind? Hannah Arendt fragt und beantwortet “Where are we when we think? Nowhere“.

Erewhon? Sind wir hoffentlich, endlich, nirgendwo?

Seda Tunç, Ohne Titel

Circumventions

Literary texts are eruptions onto the page. They are disclosures that pertain to a certain completion, a Vollendung. On the one hand, they are physical and finite apparitions; the reader encounters them as complete material and reckons with them as such. On the other hand, literary texts are open-ended stuff, completions which are constantly in the wake of revealing themselves anew, when read, never quite exhausting their meaning and force of appealing. In this sense, texts come undone to the reader.

Regardless of how we near the literary text, it is important to keep in mind that everything texts do – story, characters, composition, style, in one word, the artistic vision – takes place within the enclosure – Einhegung – outlined by the margins of the paper or document. In principle, as the famous Derrida phrasing goes, il n’y a pas de hors-texte, there is no outside the text.

Yet, in the public reception of texts, there is always a trail texts leave behind, an unspoken rest that links them to an originary moment of inception and to the author’s identity. Because texts evolve in implicit cultural contexts, which function as their reflexion surface (and as fertile soil on which texts come into being) the intricate canvas of the original text is permanently infiltrated by „outsiders” who contribute to its meaning and orientation. In this sense we could understand Borges pun that the reader recreates the literary work. So, there is no clean cut between the inside and the outside when a text is concerned.

To be sure, this observation is true for all literature, but it is even more striking for second language texts, which are systematically evaluated according to criteria that lie outside the text’s enclosure. Second language literature is viewed more often than first language literature in the light of things that aren’t specifically literary. Things like the author’s social trajectory and her*his handling of the adopted language weigh more than with consecrated first language books. And these considerations shape the appreciation of the SL work. It is much more common, for instance, that the work of a SL author is discussed in relation to the supposed conservatism or openness of the national literature than consecrated works written by first language authors. As if first language authors enjoy something like a jus soli when handling the language, owning the territory of the language by some kind of a birth right.

This intrusive framing of the SL text as not-quite literary has a history that goes back to the formation of national and international literary languages and non-native writers have long been aware of its toxic effects. Fighting this essentialism SL writers have learned to deploy literary techniques which circumvent the devaluation and regain for their works the artistic aura so cherished in the North-Western artistic world. Nonetheless, even if SL texts reach a certain level of visibility, they are not exempt from falling into the trap of cultural reception. On the contrary. In fact, many SL literary works that have enriched the international literature in the last 3 decades, including German, fall victim to the racialized reception the national literary establishments are promoting. There is a deploring poverty in theorizing SL literature as either migration-based or as cultural translation of some sort. As if the fact that the SL authors are social migrants – as many are, indeed – overarches all artistic prerequisites, rendering these latter irrelevant. As if the fact of adopting a different language in writing always falls back to a pivotal moment of choice, behind which the first language awaits, latently, to inform the second language with its exotic, enthralling cultural baggage. The misery of this double-bind is not only that theory exoticises the cultural difference expressed in the language, but that this exotization creates an expectation horizon for both reader and writer and makes way to texts that are written in the ship’s wake of this idea. Between the readership and the writer interposes the publishing house, ever more market oriented, which mediates this racialized literary relation, nourishes it, in order to sell. For a certain middle-class audience in the global North exoticism sells well.

Therefore, in the context created by globalization, I believe it is crucial to understand SL literature beyond these schemes that tacitly endorse a grammar-centric view on literature. In other words, by looking closely to SL writing we can bare witness to the displacement of the literary language shaped by the state-building process within our globalized culture.

This linguistic displacement is already happening. Under conditions of globalization global South citizens have been moving to the former imperial metropolises bringing their literary skills with them. It is no coincidence that many such writers, beside being peripheral global citizens from a socio-economic point of view, are also users of peripheral literary languages, i.e. workers in literatures which are not endowed with visibility and enjoy no artistic pedigree. The „decision“ of writing in a dominant language therefore implies strategy, considering the perspective of reaching a broader audience, bringing in more experimentation, though this often goes hand in hand with losing the native audience and many other, let’s say, artistic assets on the road.

In order to understand the literary strategy of writing in a second language I propose to retort to the genetic metaphor of mutation. Mutations are the backbone of avant-garde turns in literature. They are not restricted to SL writings. In any case, the concept of mutation presents the methodological advantage of evaluating the literary innovation within the enclosure that texts build. It leaves the outside outside. It leaves socio-cultural phenomena connected with the writing of literature (such as migration and cultural translation) to the study of sociology and cultural anthropology. Here I am interested in the mutation metaphor only from a literary-theoretical perspective on SL writing. I am interested to see how SL writers employ literary techniques in order to put their work on the map and, by doing so, how they change the rules of the game.

Sprachwechsel/Sprachwandel

Nimm diese Spielwaren. Wir spielen ein Spiel

Ich habe Angst. Was ist wenn sie mir weh tun?

Vielleicht finde ich den Weg nach Hause nicht mehr!

Sei doch nicht kindisch! Hier ist dein Haus

Hier ist nur eine Lichtung

Wenigstens regnet es nicht

Es hängen Skelette an den Bäumen

Es sind bezauberte Vögel

So etwas gibt es nicht

Du bist ein schlauer Fuchs

Hör auf mich wie ein Kind zu behandeln!

Entschuldigung

Sieh da die fetten Früchte!

Ist das der Bach des Vergessens?

Das ist ein ganz gewöhnlicher Bach!

Lüg nicht!

Gehe ich darüber, verliere ich mein Herz, nicht wahr?

Du hast schon einen Hang zum Drama, merke ich

Hier, sieh doch selbst, tauch den Fuss in das Wasser

Fass mich nicht an!

Jeder kann jede Zeit umkehren

Wenn ich mich entscheide, entscheide ich allein

Natürlich

Und schon entschieden?

Schweigen

Komm, gehen wir ein Stück gemeinsam

Sie brechen auf

Exkurs 1

das Eigene, das Fremde in der Sprache

Es heisst: meine Sprache, eure Sprache, die Sprache der Deutschen, die Sprache der Straße, der Jugendlichen, der Migrant*innen usw. Als ob die Sprache tatsächlich eine eintönige Sache wäre, reibungslos einer anonymen Multitude (wie einer Ethnie) zuzuordnen. In Wirklichkeit weiß jede Migrant*in, die gerade dabei ist, die Sprache in ihrem (Anwendungs-)Sprachraum zu lernen, dass auch Muttersprachler*innen je nach Artikulations- und Vorstellungsvermögen die Sprache biegen. Am Anfang – und manchmal in späteren Phasen des Lernprozesses – sieht sich die Migrant*in gezwungen, ihr Gehör zu schärfen, es von Person zu Person neu anzustimmen, damit der Austausch weiter erfolgen kann. Dies geschieht so, weil Sprachen lebendige Artikulationsübungen sind, die sich mit den Ausprägungen des Körpers und mit der umständlichen Location permanent färben. In dem sie im menschlichen Körper verankert ist, in dem sie von der jeweiligen Situation abhängt, entspringt die Sprache aus einer materiellen Basis und hat einen finiten Charakter. Das, was wir als persönlich in der Sprache wahrnehmen ist die spontane Durchführung auf der Zunge von Körper, Location, Ansprechpublikum etc. Migrant*innen in fremdenfeindlichen Kontexten – ähnlich wie Frauen in sexistischen, wie kolonisierte Subjekte in kolonialen Kontexten – bekommen diese materielle Komponente, die in der Sprache mitschwingt, zu spüren. Oft wird sie als Vorwand für die Entwertung der Ansprechpartner*in missbraucht. Diese Verneinung des Anderen seitens der Rassisten und Sexisten ist möglich, ohne dass die Rassisten und Sexisten jemals einwilligen, sie greifen gerade eine Person in ihrer Personhood an, weil Sprache ebenfalls etwas Über- oder Zwischenpersönliches ist. Sprachen verbinden Menschen, ohne dass sie selbst etwas Menschliches sind. In diesem Lichte betrachtet gleicht eine Sprache vielmehr einer Maschinerie oder einer Infrastruktur oder einem Reichsgebiet, wo die Güterwege mit den Militärzonen sich kreuzen, wo hie und da Aussichts- und Überwachungsstellen den Boden markieren und beleuchten. So sehr sind Sprachen in der Moderne zu Gebieten geworden. Zumal: die Zentralisierungs- und Standardisierungsmaßnahmen durch Schule, Radio, Fernseher, die Durchsetzung von Nationalsprache und –Literatur haben den Anschein erweckt Sprachen stünden gerade in dieser Welt mithilfe von ethnozentrischen Rückgräten. Vor allem in Mittel- und Südosteuropa, durch den Einfluss deutscher Romantik findet die illusorische Kupplung von Sprache und Ethnie als zwischenmenschliche-unmenschliche Struktur noch Gültigkeit. Der deutschsprachige Raum, in dem vor allem die türkische 2nd Generation erfindungsreiche Wege in die deutsche Sprache gefunden hat (kanak sprak usw.), erlebt seit zwei Jahrzehnten die Auflösung der romantischen Schema: Sprache, Boden, Ethnie wird literarisch infrage gestellt. Dennoch zweitsprachige Autor*innen der 1.en Generation werden noch immer als nicht ganz, nicht Deutsch, Sonderdeutsche behandelt. Dabei ist die intuitive (d.h. geschichtlich gewachsene) Assoziation zwischen Schreiben und Erstsprache – dass die Schriftsteller*in am besten in ihrer Muttersprache schreibt – eine unbegründete (dennoch geläufige) Annahme.

Schriftsteller*innen sind Sprachforscher*innen. Für viele ist die vorgegebene Erstsprache der Sozialisation ein Hindernis, von dem man sich lösen muss, um überhaupt zu etwas Eigenem zu gelangen. Die Literaturpraktikant*innen sind immer am Anfang auf Null in der Sprache, sie müssen die Sprache neu schmieden, so wie die Pharmazeut*in ihre Lösung vorglüht und -mischt. Für einen schreibenden Menschen, der dem Neuerungsimperativ des literarischen Feldes unterliegt, ist das, was wir üblich die eigene Sprache nennen, nichts Eigenes. So gesehen ist jede neue Übertreter*in auf dem Literaturgebiet, ein undocumented person, die um die Aufenthaltsbewilligung in der world republic of letters ansucht. Doch, da Literatur nicht demokratisch regiert wird, variieren die Wege und die Ressourcen der Ansuchenden sehr. Manche haben bereits Karte und Kompass parat, andere dürfen – aus ständestaatlichen Gründen – den Weg der Vorfahren gehen, während wieder andere sich gezwungen sehen, sich durch die Dickicht der behördlichen Hürden durchzuschlagen. Egal welchen Weg eingeschlagen wird, führt er immer von dem Befremdenden zu dem Eigenen, sonst bleibt Literatur eine Spielerei oder wie es Rabindranath Tagore einmal formulierte, sonst sind wir, die Schreibenden, wie jene Fischer, die sich im eigenen Netz fangen. Der „migrantische“ Aneignungsprozess der literarischen Sprache hat viele Nachteile – sprachliche und übersprachliche. Doch einer der Vorteile ist, dass er die Bewegung von Fremdheit zum Eigenen, von Stille zur Form in ihrer Radikalität auf sich nimmt. Mit ein bisschen Glück entstehen dabei Spracheffekte, die die Größe und Würde von Literatur vielmehr preisen als wenn man die Sprache „von Zuhause“ kann.

die andere Sprache Nummer 3

dies ist ein Liebesakt und ein Rückstellungsanspruch

der Atem sucht um seine verflüchtigten Züge

wenn es hart auf hart kommt, gehe ich lieber zur Anderen

niemand betrügt niemanden so

der Rausch des ersten Hinhörens ist Geschichte:

ich war so verliebt in sie, so fasziniert

die Gelassenheit ist auf den Fluren einer Behörde verschollen

die Norm arbeitet sich durch die Kehle mit perfiden Zangen

viele Einheimische sprechen eine Fremdsprache

irgendwann werde ich dieser Verzweiflung ein würdiges Denkmal widmen

(Nicht in der Stadt. Auf einer bescheidenen Anhöhe. Draußen)

die Raben, die mit dem Rausch in ihren Krallen davon flogen,

werden Amber aus meiner Hand picken.

wenn es mich dann nicht gibt, wird es eine Andere geben

die übernimmt

Hört über das Zischen hinweg

Dies ist ein Liebesakt und ein Rückstellungsanspruch

Aus der schrägen Umarmung kommt ein schreiendes Kind zur Welt

(und ein Ödland)

literary habitats

The English language is nobody’s special property. It is the property of the imagination: it is the property of the language itself

Derek Walcott

Language is my home. It is alive other than in speech. It is beyond a thing to be carried with me. It is ineluctable, variegated and muscular.

Vahni Capildeo, Measures of Expatriation

We could simply swap English with German in Walcott’s quotation and I would have made the first part of my point clear. But there still remains the question of how one dwells in the language or how literary habitats are shaped.

Ever since Hölderin language has become the metaphysical place of dwelling for German poets. In fact, many writers, first and second language alike, state that language is where they feel at home. Not the country, not the place of residence, not God – language. Vahni Capildeo’s above example is just one of many. It seems only natural that people whose main activity is working with the language feel most intimate in the realm of words. However it doesn’t come too natural to me to call home the place that arises when writing in the second language, German or English. Why, indeed, call home a realm whose governing laws remain partially shrouded to me, where one walks with insecure steps, afraid not to step on something friable or inflammable? Where does the need to call something home come from, which is obviously unhomely, where das Unheimliche roams unbridled? It seems to me that this inclination toward finding a new home in a language that’s acquired in adult age originates in our humanist culture which tends to humanise the experience of radical transformation. (In this case it would be more proper to say that it domesticates the transformation). Besides, there is the social pressure, oversimplistic in its readiness to “accept” new entries in the national literature, that frames the adoption of another language in writing as home coming, viewing it as an act of voluntary assimilation, as willing effort to integrate in the dominant culture. But things are much more complicated than this.

For, in fact, writing in a second language is like immersing yourself in a new medium. The act is dangerous. It can easily break the author of the act, it can drown the author. In order to survive to the complete novelty of the medium the author has to transform first and foremost her*his body. One has to grow gills to be able to breathe. And if the fins are missing on entering the ocean of the second language, the author will have to grow them, too. Whoever takes the risk of immersion is first confronted with these survival threats that need to be done away with before one moves further and starts building a habitat. Please, mind the choice of words: I say habitat, not home. Because in the process of acquiring a language in writing one becomes a different writing animal. Thus, to me, the transformation is not about becoming human, all too human. It is not about forging the skills, finding the techniques that allow you to show your human face through language so that the “others”, the audience of the dominant culture recognizes you as a human being or understands your voice as a human voice. No. The transformation unearths the buried nexus of animality and writing, shedding light on the fact that writing is first of all an act of survival in a hostile environment which requires bodily adaptation. Yes, SL literature springs up from the sheer will to write against all odds. Moreover, in the case of SL writing this adaptation happens with an unusual suddenness and vehemence. This suddenness testifies to the radicalness of the transformation. The SL leaves no room but for deep changing, yet how far this change subverts the medium the writer works with or how willing the literary work is to accept the medium is, again, a tactical choice. Weather they like it or not, works and their authors move on technical terrains where personal tastes and feelings need to be coded otherwise they fade away, discredited as personal testimonies, memoirs, childish literature. Thus, out of technical necessities that define the literary field SL people become fish again, owls, wolves, swarms of insects through writing. Incidentally, only when the mutation process is on the way, can the question of the habitat be raised.

Science defines plasmids as genetic structures that have the ability to modify the genetic content of a bacteria or the environment in such a way that the bacteria survives and further develops. The transformation occurs through various processes (transposition, conjugation), but the goal remains the same: cell’s stability in a certain environment. Similar to the plasmids the literary techniques SL writers deploy infiltrate the environment of the acquired language spawning change and innovation in the literary field. Or, simply, provoking disturbances. Literary techniques, that shape the author’s style, define characters and conflict, favor certain topics to the detriment of others etc. work as the writer’s plasmids, or else they can be understood as literary “genetic” structures which, inserted into the body of literature, guarantee the literariness of a language and ensure their survival as literary works. The queer approach by SL writing which grasps the new medium of the dominant language, so to say, obliquely make them susceptible to techniques that are different from the first language approach. Even when the result bears similarities with first language texts – meant here is that completion quality or eruption onto the page I mentioned in the beginning –, the creation process is in fact different. Taking the SL author’s point of view one could speak of building a habitat through the deployment of literary techniques. The SL author, the immersed one, once endowed with the ability of surviving in the new environment, embarks on the quest for a place of residence through the work, and sometimes for a way to change the language-environment to his*her needs, if possible. Of course, each expression of this quest for a literary habitat differs from the other and there are as many responses as are SL works.

On Agota Kristof’s literary habitat

Agota Kristof, for instance, builds herself a wolf’s lair from where she bites into French brushed up littératurisation, breaking it to pieces. Her approach resembles that of a sculptor hammering her way through the rough stoneware with rudimentary tools. She writes in French almost despite French. Which is why she says in her autobiographic essay: “Je sais que je n’écrirai jamais le français comme l’écrivent les écrivains français de naissance, mais je l’écrirai comme je le peux, du mieux que je le peux. Cette langue, je ne l’ai pas choisie. Elle m’a été imposée par le sort, par le hasard, par les circonstances. Écrire en français, j’y suis obligée. C’est un défi. Le défi d’une analphabète.” Kristof the SL author deliberately embraces the scarcity of her linguistic means which gives her style a touch of stubborn austerity. But the effect is powerful and refreshing. Agota Kristof wouldn’t have been possible as author without the French literature being ready for more austere forms of writing, for a sort of anti-literature whose terrain had in fact been prepared by the European avant-garde before and after World War II. In her case, as in the case of other SL authors, the reciprocal ties and influences with the avant-garde techniques are crucial. Which shows that there must be a strong connection between literary techniques and the literary field in order for a work to swim with the wave. Or to come back to my metaphor literary plasmids need a ripe genetic environment in which to operate successfully otherwise their actions are sterile.

On Samuel Beckett’s literary habitat

Agota Kristof’s austere mode of writing comes in stark contrast to what Samuel Beckett devised through his technique of obstinate self-translation (from English to French and vice versa), by which his detail-rich, dense texts abound in unexpected turns of phrase, here rigorous, there flamboyant. Beckett’s line of action is also in search of a habitat in the language for the writing animal that discovers itself in the process of writing in the second language. It could be easy to read many of Beckett’s major works as grand metaphors for this quest for a place, which with him is always also a quest for form, starting with that strange and marvelous text called How It Is. Beckett made a literary monument out of the author’s impossibility to abide in his*her own space of creation. Like a hunted animal the “I” of the narrative sees him*herself cast away by the net of images and thoughts it itself casts. The only way to catch a glimpse of that evasive “I” is to keep going, to carry on with the movement that disintegrates the author. So, with Beckett the writing animal is a being whose habitat is de facto nowhere, or rather who lives shortly, chimerically, in that tension words create between them and between languages, like in a shortly-glanced clearance. Beckett’s techniques, the plasmids of his bacterial-literary work, if you wish, are acknowledgments of the fact that between the “I” and the language there are only disconnections, no direct points of refraction. The embassy of his work would serve as a testimonial to this ontological language dispossession, which, tragic as it may be, can be solved through more techniques overlaid like in a wash-drawing. So, with Beckett there is this paradox: that the literary-genetic material which ensures the survival in the environment literature testifies to the impossibility of existence as a writing animal. There is no existence beyond the technicalities which the environment sustains. In other words, the bacterial effect of the work outlives the creator who dies away knitted into the fabric of the techniques.

I borrowed these two exemplary and well-known cases from the French literature to suggest that the acts of the SL writers are concerned with language, that language is the realm whereupon their works and literary techniques operate and that the techniques they deploy are survival skills as authors in search of a space of liveability in a new, partially hostile, partially engrossing environment called the second language. What brings SL texts together, despite their uniqueness and individuality, is the literary transfiguration of a sociality that is multilingual, where denominations are uncertain and sometimes confusing, where there is a permanent to and fro from one puddle of vocabulary to the next, where great geo-cultural leaps are made in a blink of an eye. Yes, it is true that SL literature’s point of departure is the transnational space of globalization, those fervid fringes where migrant, refugees’ and diasporic cultures intermingle using the dominant languages of former and current empires. However, literature is played out, so to say, on the domain of words and techniques which evolve according to an intrinsic logic of their own, a genetic pattern. Here SL writers are writing animals, athletes in spectral corporeality, who radically transform their bodies in order to survive and thrive.

Walcott’s point in the above motto is that there is de facto no linguistic or literary authority entitled to govern over language than language itself, that is the devices employed, insertions of plasmids in the literary environment. A conclusion drawn from the writing animal’s point of view who learned that literary habitats are never given, but places that need to be built. Drawing on a bodily experience.

Die andere Sprache Nummer 4

die posthumen Protokolle aus Babylon

auf einmal war das Gedächtnis dahin

sie entstieg dem Meerschaum

und verwehte die Blätter früherer Begierde

meine Ader pochte in alle Richtungen

und ich ahnte nicht,

dass sich das Leben auch auf ihre Haut einschlagen lässt

wie unter dem Abdruck eines verliebten Fingers

wollten wir das Ganze erspähen und bewandern

doch ich war der Duft einer verpflanzten Blume

und wie so oft geschiet,

wenn einen der Lärm eines gewöhnlichen Mittags einholt,

starrten wir bloß am Tisch vor uns hin

nunmehr

verwundet im Haus

und immer rasender wurde eine Tür nach der anderen zugeschlagen

(doch wenig davon kann aufgezeichnet werden)

jemand von uns muss längst die Schlüßel weggeschafft haben

denn keine kann noch das Zimmer betreten

oder jenen Balkon

aus dem sich die Stadt unserer Stirn versprach

und jetzt, wo alles hinter sich knarrt,

wo ich – also diese urkundliche, unrunde Hand – aus dem Schlam des Sturms die Blätter zu retten versuche,

komme ich mir selber vor wie ein Schreibgelehrte

dessen Kanzleisprache ihren eigenen Anlauf nimmt

unabhängig von ihm

damit sie – d.h. nicht er –

irgendeinen Wunsch, irgendeinen Erinnerungsfetzen

auf die Tontafel des großen Königs Nebukadnezar

zwischen zwei Gebote

aufdrängt.

Excursion 2

crossing the waters, not splitting the waters

Sea shores are nowadays an intoxicating mix of care free delight and absolute horror. As tourist it seems possible to stay in comfortable resorts next to the migrant routes. From the ocean’s point of view people share the same water, but the world in a crowded boat and the world in a chaise-longue, though shrouded in the same receding light, couldn’t be more different. In the vision propagated by the global capitalist culture, wide open spaces tend to be taken for metaphoric images of freedom; enjoying it from afar, the on-looking subject experiences the illusion of bringing nature under his*her control… To bend it to our consumption habits. However, freedom is not a question of view, but of practical dispositions and people venturing into the treacherous international waters know that their salvation depends on the material conditions which enable them to keep floating. One needs both skills and equipment, otherwise the water will turn into a blue grave. If conditions are unfavourable, people risk drifting off, in which case the intervention of well-equipped authorities is urgently needed.

I use the water metaphor for the practice of switching the language in writing: the comparison a bit far-fetched, since no physical danger threatens the life of the writing person as it does with the refugee. However, I find it useful to associate adopting the dominant language in writing with the gesture of subduing oneself in new waters. Water knows no boundaries, it flows uninterrupted from one world’s end to the other and it varies a lot. Water changes its composition, it can be salty, sweet, deep, shallow, lapis lazuli-like and dark as the orca’s fin. For humans it is both life sustaining and death-bringing. Against the work of the grammar experts, who broke their backs in order to separate languages from one another, to ascribe them autonomous, internal rules, languages maintain their watery qualities. They intermingle and combine, creating momentary waves, with their specific hues, sounds and texture, like the water spray of a fountain on a hot summer day. Even when the tongue is formally fully mastered, underneath its skin run the underwater currents of silenced, translated, transboarded signs and images, that do not find the actualized form, so that they can, too, go with the flow. This does not intend to suggest that language oceans are free sailing territories. Like in real life, in watery languages, too, there are national and international agencies. And the water surface is parcelled out in territorial seas, coastal and international waters and so on. Contrary to the widely spread view of the artist floating in a free world, in art-related matters, too, one still needs papers to cross over. In literature, which works with such a democratic material like the spoken and written word – and the word, at least in theory, belongs to everyone – one has to convince the gate keepers that the thing one does is truely literature. Such is the rite of passage in the literary business, almost magical (validating criteria are covered up) – if it weren’t for the market oriented criteria which take hold ever more, and with ever greater efficiency on the literary product. Anyway, in order to ensure the crossing, it always helps to know a thing or two about the seas into which one ventures, otherwise the goods on the raft might dry out waiting in line for the permit. Sadly, few warnings prepare the crossers for the hardships of crossing the waters. The honeyed sirens of the free world-language whistle their song so sweetly, that when confronted with the coercive apparatus installed by the supervising agencies, the crosser is left with conflicting feelings of bewilderment, distrust, anger, anguish. In an equivocal, on-hold position. Water is a dangerous material to play with, because es sickert in alle Risse des schreibenden Subjekts hinein, the human soul has no membrane for it to keep it at bay, and when the prohibited character of certain waters get the upper-hand, they transform the person dramatically. Even to the point that the voice does not recognize itself anymore. The effect of such destitution is silencing or the retreat into the ”safe space” of the mother tongue, provided that the ”original” space was not washed away by water in the meantime. Both ways – going back, moving farther offshore – are legitimate; through them one can regain the lost equilibrium, find some breathing space again. However, if one finds the strength to pursue the crossing, then the waters stop splitting up and they come together as they actually are, fluid-fluent, ineinander-fliessend, not belonging to a territory, but to a specific productive act, like water-sprouting or immersion. Only in this sense, languages give a home to the writer – as a practice, which is transgressive and enacted. And erkämpft von unten, from the basement level, where words are word shreds, latent possibilities barely heard.

For the writer paddling out into the dominating ares, there is one other thing to do, once the transgressive stage is reached. In order to keep the wheel spinning, he or she has to somehow come to terms with the language of domination. One way of doing it is to go back to that initial thrill of discovery, which gave the first impetus for jumping in. It’s always good to reclaim one’s own tools that have been plundered by the imperial power, when possible. And then, one has to let go to the humiliations, deprivations and to the injustice felt all the way through the long process of getting across to the other side. Not that one has to forget or repress, but water is a medium that doesn’t take sides, if stirred well, it reaches out and moulds any kind of shore according to its own wishes and power.

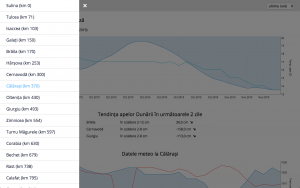

Second Language Plasmids. Fig 1

Second Language Plasmids. Fig 1b

Excursion 3

on taking pleasure in the language

I don’t believe one can sustain writing on the long run without finding a way to enjoy it. To the serious play, that is literature, the fun and the pleasure in the language is like the oil that lubricates the engine, so that the engine doesn’t crack. Some combustible has to be burned for the act to keep going and pleasure (alongside hard work, focus, determination) keep the joints in their place. However, I wouldn’t go so far, as some of the postcolonial writers do, as to speak of love – loving the tool one works with, that is the dominant language. It is very possible that the language shifter feels at ease (and at home) in the second language only after the overwhelming act of acquiring, settling and performing the language has been accomplished. If the learning scars are still fresh, as they are with many migrants, the uneasiness stays with the speaker.

Incidentally, in dominated cultures only kids that have a certain social endowment enjoy the privilege of learning the respective dominant language from an early age. (They can burry those memories under the layer of proficiency achieved during childhood). For them there are private teachers, language institutes, colleges and so on; for all the rest, they would come in touch with the dominant culture (and its language) later in life, mainly under concrete, instrumental circumstances. And if the situation requires or if they have an inclination towards it, they will try to catch up on lost time and surmount the impairment. The relative social safety in which rich kids of the dominated cultures get to know the second language couldn’t contrast more with the precariousness of the learning conditions for the rest of their fellow countrymen. Roughly sketched, the latter adopt the language as adults, while performing other works in addition to acquiring the language. In the Global North, still so much fueled by white male supremacist phantasies, they have to put up with exclusion based on language (either you don’t know it well enough, or you don’t pronounce it according to the local standards). For the vigilant ear, which polices the new entries in the language, it is never good enough. Adding to this the paper work, one has to go through, in order to secure a legal status for oneself, a work permit, the right to reunite with the family and so on, the degree of difficulty in acquiring a literary competence in a second language becomes clearer. If the language switcher stays true to the experience, his or her voice would reverberate on the page in such a way that it would turn on that unheimliche Welt and make it speak. Personally, I envision a language like a staccato musical piece, full of dissonances, gaps and blanks that have to be filled in by the readers. In literary matters though, every one walks their own path according to their tools and desires. Anyway, due to the fragile environment in which the dominant language sprouts, the violence (das Gewalttätige und das Gewaltige) of words bursting out into language always lurks on the surface ready to be disclosed. Since the birth of the literary work in a second language is closely linked to its negation as an art form (through silencing, estrangement, devalidation etc.), neither love nor pleasure, but insecurity, anger, apprehension, outrage are the mobilizing feelings behind it during its first phase. Productive as these feelings may be (not to mention their legitimacy), they cannot last indefinitely. At a certain point in his*her development as a writer, the language switcher has to find the key to the door leading back (or rather forth) to desire.

Literature is a game – serious, but still a game. And the raw material that sustains this game, i.e. language – be it the first, second, third, and so on – grows when it’s handled freely. I claim that meaningful literature comes out of this conciously, skillfully played game. Writing in more languages from an engaged dominated position attests to the transitional and transgressive character of languages. If so, with them there always comes the threat of dissolving into unhomely silence. Nevertheless, against the perils of unhomeliness, literature can build habitats, protective sheaths, that are no Heimat. For that – for the Heimat – there are enough external props, mainstream instutions and so on. I’d rather plead for something more modest and fragile, a snail’s shell. Something based on the right to crawl in and reshape the ossified crust. Inclusion, yes. But inclusion on such terms, that are non-humanistic and do not pretend to know beforehand what a human being is. Standing up to the transnational life-challenges in this financialized world compels the vulnerable subject to pick up the broken glass pieces anyway. One has to walk into the shadows. But the road leading there, at those crepuscular foundations laid on shifting waters, goes through pleasure. For losing pleasure in language means losing the ground on which one can pause for a breath. Being a thing that is alienated by the force of the cultural-colonial gaze, pleasure needs to be fought back constantly in writing. This is just a specific challenge in writing, one among others. Like other challenges, it is both exhausting and thrilling.

Übersetzbarkeit

“Wo gehen die Dinge verloren, Bruder?”

“Ich bin nicht dein Bruder”

“Wo sind das Spielzeug, die wollige Decke,

der Kindheit tröstlicher Nachmittag?”

“Sei doch nicht unverständlich”

“Siehst du! ich hebe die Arme zu dir”

“Was?”

“… und trete hinüber”

“Die Brücke ist verbrannt.

Lass doch lieber los.

Erst im Fall erreicht man den Boden.

Verstehst?

Verstehst?”

über Paul Celan’s literarisches Habitat

Ruth Lackner, Schauspielerin im Jiddischen Theater in Tschernowitz und Freundin des Dichters, die im Übrigen, wenn mich das Gedächtnis nicht irrt, Celan vor der Deportation in das Nazi-Lager gerettet hat, erinnert an den folgenden Satz von Celan, den er ihr eines Tages gesagt haben sollte:

“Nur in der Muttersprache kann jemand seine eigene Wahrheit sagen, der Dichter lügt in einer Fremdsprache”

Die Aussage wäre bloß eine Anekdote, wenn sie sich nicht auf das Werk von Celan stützen würde. Celan hat tatsächlich die Sprache der Mutter gewählt. Die Mutter, Friederike Antschel, hat das europäische Ansehen des Hochdeutsch gegenüber den anderen vier Sprachen, die in Tschernowitz gesprochen wurden, bevorzugt. Der Sohn folgte ihr in der Lyrik.

Ich würde gerne Celan fragen, ob seine absolute Einsprachigkeit, die er im Schreiben hochschätzt, keinen Tyran in seine poetische Werkstatt eingelassen hat. Jemals. Einen Tyran, einen Zensor, eine Wort- und Bedeutungspolizei. Ob er niemals beim Schreiben gefühlt hat, dass er etwas verliert, auslässt, verwindet, verlässt usw. in dem er alles einer einzigen Sprache umschreibt.

Mir ist es bewusst, dass die Art wie er die deutsche Sprache angefasst, nämlich quer, und sie verbogen, und so ihre Ausdrucksstärke erweitert hat, ist seine Art auf die Frage indirekt zu antworten. Celans Sprache umwälzt jene Nazi-Verwaltungssprache, durch deren Anwendung die Nazis ihre Verbrechen ausgeführt haben. Dem politischen Engineering der Nazi-Sprache setzt Celan das poetische Engineering, die einzigartige Sprache des Individuums. Es ist, zweifellos, ein Aneignungsmanöver. Man hat viel darüber gesprochen. Ich weiß nicht jedoch ob er sich jemals die Frage gestellt hat, woher bei ihm die Glaube an die untrennbare Bindung zwischen dem Dichter und der Muttersprache kommt, woher diese unausweichliche Monoamorie zwischen dem Dichter und seiner Sprache, bei ihm, der mehrsprachig aufgewachsen war in einer Welt, wo Jiddisch sich mit Hochdeutsch vermischte, mit dem Rumänischen, dem Ukrainischen und Russischen. Ebenfalls weiß ich nicht ob er irgendwo in seinem Werk auf diese Frage zurückgekommen ist, die mir entscheidend für seine Dichtung erscheint.

Was mich angeht, ich glaube, dass jede*r von uns mehrere Sprachen in uns trägt. Und die Grenzen zwischen ihnen sind durchlässig. Auch wenn wir aus der Sicht der Grammatik eine einzige Sprache sprechen, sind die Sprachregister, die wir dabei anwenden, mehrfach. Wir haben keine Muttersprache, sondern viele Sprachhebammen. Eigentlich Sprachinfrastrukturen (um aus dem familiären Umfeld auszutreten). Die Dichtung inspiriert sich an diesen verschiedenen Registern die, angelegt, dosiert, den Kompositionsregeln unterworfen, zu jener “eigenen Wahrheit” gelangen, von der Celan gesprochen hat. Celan, gewiss, hat die poetische Sprache von der Sozialisation abgelöst und zugleich hat er sie von der Nazi-Erbe befreit und enteignet. In einem Zug wurde die Deutsche Lyrik von der romantischen Last befreit, die sie noch am Boden gebunden hielt (und vom Deutschtum und anderen Residuen des Bildungsprozesses der deutschen modernen Identität). Durch Celan wird Dichtung, vielleicht wieder, zur einen Auseinandersetzung des Individuums mit dem Ort des Daseins – mittels der Sprache.

Und doch lässt Celan eine einzige Sprache im poetischen Labor zu. Und auf diese Weise, stillschweigend, verlängert er das modernistische Paradigma, das die Sprachen voneinander abtrennt. Er macht sie zu eigenständigen Gebieten, mit eigenen Regeln ausgestattet (mit Grammatiken), mit Expert*innenstimmen (Dichter*innen, Schriftsteller*innen) die aus denen voller intimes Wissen hervorkommen. Celans Dichter, so scheint es mir, ist ein solcher Experte der Eigensprache, die er sondiert so wie ein Erzaufsucher nach Erz tief in der Erde sucht, er ist der einzige Machthaber seines existenziellen Gebiets dessen Grenzen er überquert um uns zurückzubringen, – umgesetzt und verschoben – die Worten. Doch die Worten können nur in der Logik einer sphärischen Sprache umgesetzt werden, einer Sprache die sich ständig auf sich selbst bezieht, auch wenn sie sich erneuert und anreichert, bleibt sie eine Monade. In einer gewissen Hinsicht ist Celans Werk (wie das Werk von Beckett im Übrigen, aber das ist eine andere Diskussion) aus diesem Grunde eine Endstation im Zeitalter der Globalisierung. Sie schliesst einen Weg am Grenzgebiet des europäischen Modernismus. An ihrem Ende steht, wie eine zugemauerte Tür, die poetische Einsprachigkeit. Eigentlich ein Paradox! Es ist nicht zufällig, glaube ich, dass Celan von den Anhänger*innen der Grossliteratur gelesen und zitiert wird und von dem Kulturestablishment. In der postkolonialen Literatur wird selten auf ihn hingewiesen. Ebenso verhält es sich mit den ZS Autor*innen, den wenigen die zur Sichtbarkeit gelangen: die kommen über andere literarische Genealogien. Vermutlich wird die Dichtung der Globalisierung allmählich das mehrsprachige Paradigma begrüßen, das so präsent in der postkolonialen Literatur ist, wo der Austausch zwischen Englisch und den ehemaligen kolonisierten Sprachen lebhaft geführt wird. Wir werden immer mehr Dichtung schreiben wie die Dichter*innen am Hof der Moguln in Hindustan, die das Persische mit dem Arabischen, mit Urdu und anderen Sprachen abwechselten und aus allen gestohlen haben. In diesem Kontext können die Fülle von Celans Sprache und seine dichten und überraschenden Bilder zu einer Inspirationsquelle werden, jedoch nicht seine programmatische Einsprachigkeit.

anfängliche Terror

wir gehen unter dem schwarzen Himmel spazieren

beinahe Schulter an Schulter,

der Wind bläst ins Gesicht,

die Sterne liegen unter den Füssen.

Nun, einen Platz unter der Sonne,

wo findet man ihn

gemeinsam?

Du, zart wie noch nie zuvor,

machst mich zur Frau,

doch ich bin nicht diese Frau

und du machst mich zum Kind,

doch ich bin nicht dieses Kind

und du machst mich zum Gleichen

doch andere Böden halten mich.

So, vertieft im Gespräch,

rühren wir Alles Erlaubte,

als rührten wir in einer Teeschale

im Garten deines Hauses.

Und nur über das Schwert

in meinem Schenkel begraben

müssen wir hinwegsehen,

denn er will mich von innen erleben,

mein Geliebter,

und ich will ihn haben,

mit seinem Reich von Gütern.

So gehen wir spazieren

unter dem schwarzen Himmel

ohne an die Wunde zu rühren,

wo Krieg herrscht und wahre Liebe erst beginnt.

Exkurs 4

über die Sprache durch die Sprache hinaus

… eine Sprache ist nicht nur die normierte Artikulation von Lauten. Sie ist vielmehr eine Ordnung von Bildern, Gefühlen, Ideen usw., die kollektiven Ausdruck in der Sprache finden. Jede der_die den Sprachwechsel in die dominante Sprache vollzieht, weiß, dass jene erste Welt, unter deren Dach mensch sich einst zuhause fühlte, schwindet. Die große Hürde besteht nicht darin, die andere Sprache zu erwerben. Auch wenn dieser Akt einen enormen persönlichen Aufwand benötigt, wiegt er weniger schwer aus literarischer Sicht (eigentlich ist er bedeutungslos) als der Versuch sich einen Platz in der neuen Sprachwelt zu schaffen. Das Verhältnis zwischen der dominanten und der dominierten Literatur erduldet aber keine Übertragung von Themen, Motiven, Literaturgenres-, Techniken usw. aus der dominierten in die dominante Sprache. Anfangs stellt das eine große Herausforderung für dominierte Schriftstellerinnen dar. Meist werden diese Übertragungsversuche, wenn sie passieren, als nicht-künstlerische Akte behandelt. Sie werden schubladisiert und untergeordnet. Oder sie werden als Rückstandsbeweise ausländischer Literatur betrachtet. Aber so eine Entrechtung beim Grenzübergang zwischen den Sprachen hat auch ihre Vorteile. Im günstigen Moment – und nur wenn die Ausdauer nicht ausfällt – kann diese die Sprachwechslerin zu radikalen Eingriffen zwingen, die das literarische Feld erneuern. Dass diese Erneuerungen als Hybridisierung, als writing back to the empire, als Sprachaneignung usw. im Nachhinein eingestuft werden, hängt von dem unerschöpflichen Vermögen des menschlichen Ausdrucks ab – und von dem Kontext in dem jeder literarische Kampf ausgetragen wird.

… die Wege, durch die mensch in eine neue Sprache kommt, färben den Umgang mit der Sprache. Wenn jemand beim Sprechen in der Restaurantküche abwäscht oder den Glanz eines gewölbten Raums in der Akademie bewundert… das bleibt nicht ohne Folgen für das Schreiben. Mir kommt in den Sinn der Lärm in der schweizer Uhrenfabrik, mit dem die Arbeiterinnen – darunter Schriftstellerin Agota Kristof – leben und sprechen mussten. So was hinterlässt Spuren. Die Sprache wird zerfetzt, sie würgt; in ihrem Gebrauch spiegeln sich die hierarchischen Verhältnisse wider. Wut, Hoffnungslosigkeit, Ausgleichsansprüche. Solche Erlebnisse sind unvermeidlich in einer Situation, in der der Spracherwerb Hand in Hand mit einer wirtschaftlichen Unterordnung geht. Unter den Flüchtlingen, Migrantinnen, displaced persons auf dem globalen Markt gibt es heute viele potenzielle Schriftsteller, die mit den ungeheuerlichen Hindernissen der Unterwerfung zu kämpfen haben, um zu Autorenschaft zu gelangen. Ob es ihnen gelingen wird, hängt es von der Demokratisierung des Literaturbetriebs ab (international wie auch in den jeweiligen nationalen Literaturbetrieben der sogennanten Grosssprachen). Es hängt auch von der eigenen Ressourcen – Zeit, Ausdauer – ab. Und von Glück. Dass die Lebensumstände, die literarische Produktion erschweren oder erleichtern, liegt auf der Hand. Meist führt der soziale Weg in die Literatur über unterbrochene Leben, Leben deren Träume an einem Ort geboren und an einem anderen erfüllt werden, wenn sie jemals in Erfüllung gehen. Wenn mensch dazu zählt, dass die dominante Sprache(-n) erst in den Erwachsenenjahren gelernt werden, oft ohne formelle Ausbildung, manchmal nach der Anwendung anderer Regionalsprachen (kriegs-, wirtschafts-, politisch bedingt), bis alles in einem schmerzvollen, reizvollen Babylon gipfelt – dann hat mensch the whole picture. Die Hoffnung ist in der Demokratisierung des Literaturbetriebs. Eine weitere Hoffnung ist aber auch in der Demokratisierung des Umgangs mit den dominanten Sprachen – jede individuell in seinem und ihrem Atelier. Oder kollektiv. Schließlich ist ein Gewinn für alle, wenn die Verletzlichkeit und die sporadische oder systemische Gewalt, die im sozialen Feld erlebt wird, sich in literarische Mittel verwandeln. Weil weniger Gewalt dann in Wirklichkeit.

Entstellung

Ich habe kein Gesicht

die Schakale haben mein Herz aufgefressen

in wabenartiger Süße triefte das Gesang in das Ohr

ich war einer dieser Matrosen, der vom Deck ins Meer sprang

der Norden? Der ist ein einsamer Berg

die Münzen sind gefälscht

nun pinkele ich an jeder Ecke wie ein Straßenhund,

der ich bin (zu dem ich gezügelt war)

dieses Werkzeug wird in der Fremde geschmiedet

mein Onkel trat in das Haus mit dem Hammer in der Hand

meine Schwestern polieren den Gehsteig auf der Raststation

Ich habe kein Gesicht

doch ich piepe in den Garten mit diesem schiefen Blick

am Fuße vom Sockel sieht man leicht unter die Toga der Statuen

so bin ich durch die Hintertür in die Gegenwart geschliechen

und frage:

wieviel schwerer darf eine Ware wiegen als ein Atem?

Meine Hände sind sauber

der Rausch von Birken hallt das südliche Meer

für diesen Alltag wird man keine Rechtfertigung finden

Ich habe kein Gesicht

Das, was sie sehen ist eine Maske beim Zirkus

lasst doch die Bären tanzen – lacht jemand im Publikum?

Einer Höhle in den Bergen ist die Fackel kein Ersatz für die Sterne

Auch unsere Kinder baden ab und zu im Himmelsbecken

Ich habe kein Gesicht

Meine Zunge darf sich bedienen

Alles, was den Hunger eines Gespensts stillt, ist erlaubt.

Wehe Wind!

So viele Leben haben sich diesen Ort als Treffpunkt gegeben

Postkoloniale und zweitsprachige Literatur

Demokratisierungsprozesse

Postkoloniale und zweitsprachige Literaturen unterscheiden sich voneinander, auch wenn beide Literaturspalten vieles gemeinsam haben. In erster Linie teilen sie den Wunsch den Western Canon zu erneuern und vielleicht ihn dabei zu brechen. Ebenfalls teilen sie den Durst und Drang auf ein neues Vokabular, das andere Lebensformen widerspiegelt, Lebensformen die die klassische Literatur lange ignoriert hat. Was sie andererseits voneinander unterscheidet ist der Bezug auf die Sprache, denn während sich die postkoloniale Literatur auf eine institutionalisierte Sprache bezieht, eine Sprache, die geschichtlich in den Schulen und Ämtern des kolonialen Apparats verankert ist, kämpft die zweitsprachige Literatur im Namen von einer Sprache, die gesellschaftlich und geschichtlich außerhalb von etablierten Institutionen lebt. Sie lebt sehr wohl in Freundschaften, familiären Beziehungen und Arbeitsverhältnissen, aber nicht in Schulen und Verlagen. Im deutschsprachigen Raum kommt die Kanak Sprak am nähesten einer postkolonialen Sprache im Englischen Sinne des Wortes, denn die Kanak Sprak Literatur bezieht sich auf einen Soziolekt, die im Zuge des neokolonialen Erwerbs von Arbeitskräften nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg sich entwickelt hat. Im Gegensatz dazu repräsentiert die zweitsprachige Literatur keinen homogenen Sprachgebrauch. Sie entspringt vielmehr einer Multitude, wo jede*r seine und ihre eigene Gebrauch von der dominanten Sprache macht, wo jede Artikulation der eigenen internen Gebot folgt. Die zweitsprachige Literatur kennt ebenso viele Ausprägungen wie es Strategien gibt, sich in einer nicht-native Sprache auszudrücken. Im Prinzip ist ihre Ausdrucksform unendlich wie die Literatur selbst.

Die Mutation Metapher hat in diesem Kontext als bildhaftes Hilfsmittel gedient zu zeigen, dass das Schreiben in der Zweitsprache ein technisches Prozedere unterstellt wie jede andere literarische Tätigkeit, die einer verschiedenen sozialen Genesis unterliegt. Die Besonderheit der zweitsprachigen Annäherung besteht darin, dass die Sprachwechsler*in gezwungen ist, radikale Massnahmen zu treffen, damit ihr*sein Werk zur Sichtbarkeit gelangt. Aus diesem Grund rührt die Ausgangslage der Sprachwechsler*in am avantgardistischen Grenzgebiet. Avantgardistische und zweitsprachige Arbeitsmethoden sind strukturell verwandt, auch wenn dies sich für den zweitsprachigen Text als ein Schwert mit zwei Klingen erweisen kann. Denn das literarische Kapital der Zweitsprache in der symbolischen Hierarchie von Literaturschulen noch immer unten liegt. Trotzdem, wenn das zweitsprachige Werk sein volles Potenzial enthüllt, d.h. wenn es einen freien Umgang mit der dominanten Sprache erstrebt, wird das Werk zur Erneuerung führen. Allerdings werden Erneuerungen nicht einfach angenommen, sondern sie unterliegen einer strengen literarischen Codierung, die ich hier mithilfe von der Mutation Metapher zu erläutern versucht habe. Einfache Befreiung von und Ungezwungenheit im Umgang mit der dominanten Sprache ist bei weitem unzulänglich für gute Literatur.

Gute, also wirkungsvolle literarische Werke in der ZS wirken ein wie bakterielle Strukturen. Mit der Zeit verändert ihr Stoff das genetisch geprägte Umfeld – und die Genetik wird noch im deutschsprachigen Raum von der untrennbaren Anschluss zwischen Nation und Sprache geprägt. Trotz allen Fortschritten in Deutschland-Österreich wird es noch im Schatten von Herder geschrieben und gelesen. Literarische Techniken, die am radikalen Schwung der Zweitsprachigkeit ansetzen, haben das Potenzial sich in Werke einzufügen, die allmählich das literarische Deutsch verändern, ähnlich den Plasmiden im genetischen Modell. Veränderung und Weiterveränderung bis Walcotts Anmerkung auch für Deutsch zu einer Selbstverständlichkeit wird. Denn erst wenn die Besitzrechte auf die literarische Sprache in der Sprache selbst verortet werden wird die Rezeption von ZS Texten demokratisiert.

Ovid Pop, Juni-Juli 2020

Förderung durch die Stadt Wien Kultur